During what many archaeologists call the

formative period, Amazonian societies were deeply involved in the emergence of South America's highland agrarian systems, and possibly contributed directly to the social and religious fabric constitutive of the Andean civilizational orders.

In 1500, Vicente Yáñez Pinzón was the first European to sail into the river.

Pinzón called the river flow

Río Santa María del Mar Dulce, later shortened to

Mar Dulce (literally,

sweet sea, because of its freshwater pushing out into the ocean). For 350 years after the first European encounter of the Amazon by Pinzón, the Portuguese portion of the basin remained an untended former food gathering and planned agricultural landscape occupied by the indigenous peoples who survived the arrival of European diseases. There is ample evidence for complex large-scale, pre-Columbian social formations, including chiefdoms, in many areas of Amazonia (particularly the inter-fluvial regions) and even large towns and cities.

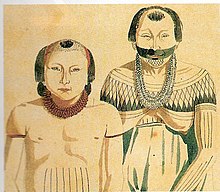

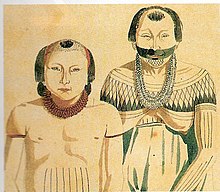

For instance the pre-Columbian culture on the island of Marajó may have developed social stratification and supported a population of 100,000 people.

The Native Americans of the Amazon rain forest may have used Terra preta to make the land suitable for the large scale agriculture needed to support large populations and complex social formations such as chiefdoms.

One of Gonzalo Pizarro's lieutenants, Francisco de Orellana, set off in 1541 to explore east of Quito into the South American interior in search of El Dorado and the "Country of Cinnamon".

He was ordered to follow the Coca River and return when the river reached its confluence. After 170 km, the Coca River joined the Napo River (at a point now known as Puerto Francisco de Orellana), and his men threatened to mutiny if he followed his orders and the expedition turned back. On 26 December 1541, he accepted to change the purpose of the expedition to the conquest of new lands in the name of the King of Spain, and the 49 men built a larger boat in which to navigate downstream. After a journey of 600 km down the Napo River, constantly threatened by the Omaguas, they reached a further major confluence, at a point near modern Iquitos, and then followed what is now known as the Amazon River for a further 1200 km to its confluence with the Rio Negro (near modern Manaus), which they reached on 3 June 1542. This area around the Amazon was dominated by the Icamiaba natives, who were mistaken for fierce female warriors by the members of the expedition. Orellana later narrated the belligerent victory of the Icamiaba “women” over the Spanish invaders to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, who, recalling the Amazons of Greek mythology, baptized the river Amazonas, the name by which it is still known in both Spanish and Portuguese. At the time, however, the river was referred to by the expedition as Grande Río ("Great River"), Mar Dulce ("Freshwater Sea") or Río de la Canela ("Cinnamon River"). Orellana claimed that he had found great cinnamon trees there, in other words a source of one of the most important spices reaching Europe from the East. In fact, true cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum) is not native to South America. Other related cinnamon-containing plants (of the family Lauraceae) do occur and Orellana must have observed some of these. The expedition continued a further 1200 km to the mouth of the Amazon, which it reached on 24 August 1542, demonstrating the practical navigability of the Great River. This was surely one of the most improbably successful voyages in known history.

In 1560 another Spanish conquistador, Lope de Aguirre, made the second descent of the Amazon.

In 1637–47 the Portuguese explorer Pedro Teixeira was the first European to ascend the river from Belém, near the mouth, to Quito, part of the Spanish Viceroyalty of Peru, and then to return the same way. Teixeira's expedition was massive—some 2000 people in 37 large canoes. From 1648 to 1652, António Raposo Tavares lead one of the longest known expeditions from São Paulo to the mouth of the Amazon, investigating many of its tributaries, including the Rio Negro, and covering a distance of more than 10,000 km (6,214 mi).

In what is currently Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela, a number of colonial and religious settlements were established along the banks of primary rivers and tributaries for the purpose of trade, slaving and evangelization among the indigenous peoples of the vast rain forest, such as the Urarina. Father Fritz, apostle of the Omaguas, established some forty mission villages. Charles Marie de La Condamine accomplished the first scientific exploration of the Amazon River.

Many indigenous tribes engaged in constant warfare. According to James Stuart Olson, "The Munduruku expansion dislocated and displaced the Kawahib, breaking the tribe down into much smaller groups... [Munduruku] first came to the attention of Europeans in 1770 when they began a series of widespread attacks on Brazilian settlements along the Amazon River."

The Cabanagem, one of the bloodiest regional wars ever in Brazil, which was chiefly directed against the white ruling class, reduced the population of Pará from about 100,000 to 60,000.

The total population of the Brazilian portion of the Amazon Basin in 1850 was perhaps 300,000, of whom about two-thirds comprised by Europeans and slaves, the slaves amounting to about 25,000. The Brazilian Amazon's principal commercial city, Pará (now Belém), had from 10,000 to 12,000 inhabitants, including slaves. The town of Manáos, now Manaus, at the mouth of the Rio Negro, had a population between 1,000 to 1,500. All the remaining villages, as far up as Tabatinga, on the Brazilian frontier of Peru, were relatively small.

Four centuries after the European discovery of the Amazon river, the total cultivated area in its basin was probably less than 65 square kilometres (25 sq mi), excluding the limited and crudely cultivated areas among the mountains at its extreme headwaters. This situation changed dramatically during the 20th century.

Four centuries after the European discovery of the Amazon river, the total cultivated area in its basin was probably less than 65 square kilometres (25 sq mi), excluding the limited and crudely cultivated areas among the mountains at its extreme headwaters. This situation changed dramatically during the 20th century. On 6 September 1850 the emperor, Pedro II, sanctioned a law authorizing steam navigation on the Amazon, and gave the Viscount of Mauá (Irineu Evangelista de Sousa) the task of putting it into effect. He organized the "Companhia de Navegação e Comércio do Amazonas" in Rio de Janeiro in 1852; and in the following year it commenced operations with three small steamers, the Monarch, the Marajó and Rio Negro.

On 6 September 1850 the emperor, Pedro II, sanctioned a law authorizing steam navigation on the Amazon, and gave the Viscount of Mauá (Irineu Evangelista de Sousa) the task of putting it into effect. He organized the "Companhia de Navegação e Comércio do Amazonas" in Rio de Janeiro in 1852; and in the following year it commenced operations with three small steamers, the Monarch, the Marajó and Rio Negro. During what many archaeologists call the formative period, Amazonian societies were deeply involved in the emergence of South America's highland agrarian systems, and possibly contributed directly to the social and religious fabric constitutive of the Andean civilizational orders.

During what many archaeologists call the formative period, Amazonian societies were deeply involved in the emergence of South America's highland agrarian systems, and possibly contributed directly to the social and religious fabric constitutive of the Andean civilizational orders.